/

Informal Upright Acer palmatum/Japanese Maple bonsai by Harry Harrington in early Spring

Informal Upright Acer palmatum/Japanese Maple bonsai by Harry Harrington in early Spring

The basic Japanese tree forms have evolved over the years as a way of categorising bonsai and also helping to establish basic guidelines for styling trees.

These form definitions are helpful to the beginner to help develop an eye for different tree shapes and to help define different trunk and branch patterns.

It is very useful for the beginner to start his or her bonsai styling education by learning these basic forms. However, once learnt, the enthusiast must not make the mistake of being bound by these definitions either.

Forms Vs Styles

In many textbooks, the following forms are described as bonsai styles, however there is a strong movement, instigated by Walter Pall, to make a distinction between the form (according to the predominant feature or direction of the trunk) and the style (the manner in which the form is displayed), and for this reason this article follows this re-categorisation by listing bonsai forms.

In summary: The form describes the basic shape of the tree as defined by trunk, the style describes the way in which the tree has been styled (for instance windswept, near or far away from the viewer, naturalistic or abstract).

Bonsai Forms Described

This is a list of the basic bonsai forms but is by no means a complete list of all bonsai forms or the many variations of the different forms that exist.

Informal Upright Form

This form is the most commonly seen in Bonsai and in nature. It can be used for most tree species. The trunk can twist, turn and change direction with a number of bends along its length though the growth is basically upwards.

Branches tend to emerge from the outside of bends. Branches emerging directly from the inside of bends often look awkward. The overall silhouette of an informal upright is often irregularly triangular but does not have to be.

Coniferous species such as Pines and Junipers are often seen with largely horizontal branching and clearly defined ‘clouds’ of foliage.

Deciduous and broadleaf species such as Elms, Maples and box should have predominantly naturally ascending branching and should not have clearly defined foliage pads; a too-common mistake is for deciduous species to be styled with horizontal branching, clearly defined foliage pads and ‘pompoms’ of foliage.

Bonsai styled in this way are too-commonly seen in bonsai books and are the result of poor and over-simplified attempts at bonsai styling.

Informal upright wild English Oak. Note this does not have a triangular silhouette.

Formal Upright Form

In this form the trunk is completely straight and upright. Previously a popular form but now much less commonly seen as the majority of upright bonsai have some movement that make them informal uprights.

Ideally the trunk should display an even taper from base to apex. This form replicates trees growing unimpeded in open growing conditions without competition from other trees. The branches leave the trunk alternatively from left to right to back and no branches face the front until the top third of the tree. All the branches will be mainly horizontal or slightly drooping as if weighed down by snow in winter. This can be a difficult form to carry out convincingly and it is recommended that only trees with a naturally straight trunk be used. The silhouette of a formal upright is triangular though not strictly symmetrical.

Deciduous species are unsuitable as formal uprights. Coniferous species such as yew, swamp cypress and cryptomeria make good candidates.

.jpg)

Formal Upright Form Taxodium distichum/Swamp Cypress bonsai by Harry Harrington

Broom Form

The broom form replicates the way many deciduous trees grow in nature given ideal growing conditions with no competition from other trees. It is particularly recommended for fine branching species particularly Ulmus and Zelkova but all deciduous and broadleaf tree species are suitable. The broom form is not suitable for coniferous species including pines and junipers.

The broom form can be further divided into two types, the formal and the informal broom.

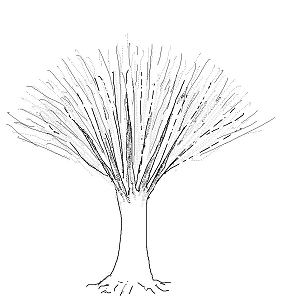

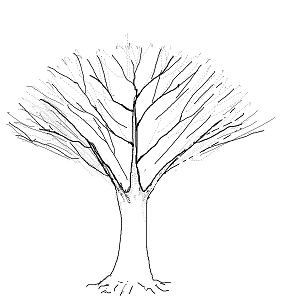

Formal Broom Form

The best known broom form has a main trunk that divides at a certain point into three or more branches of roughly equal thickness which grow out diagonally upwards from the central trunk.

The silhouette of the tree resembles an upturned Japanese broom ; hence the name.

.jpg)

Classic Formal Broom Chinese Elm by Harry Harrington

The main trunk of the formal broom tends to be 1/3 of the overall height of the bonsai. There are no horizontal branches; all branching is placed diagonally in a fan-shape with no, or very few, crossing branches.

There are variations of the classic formal broom; there can be a main trunk that runs from base to apex of the tree. However, unlike a (in)formal upright, the branches are nearly as thick and dominant as the central trunk, but all of these branches are placed at upturned diagonals from the main trunk, forming a broom silhouette.

(left) Classic formal broom and (right) a variation of the classic formal broom

Informal Broom Form

There is no reason why a tree without a straight trunk cannot be used for the broom form; a trunk with bends or movement is simply an informal broom. Quite possibly the most common form of broom seen in nature.

Field-growing Oak with an informal broom form

.jpg)

Common Hawthorn/Crataegus monogyna bonsai by Harry Harrington in the Informal Upright Broom Form

Slanting Form

In this form the trunk itself slants as though growing toward the light or as though exposed to strong wind. The trunk can be straight or curved with branches on the sheltered side lower than their counterparts on the other side of the trunk. An important feature with this form is that the nebari or roots should appear to anchor the tree to stop it ‘falling’. The roots on the side to which the tree leans should be short and compressed whilst the roots on the opposite side should be strong and dominant, anchoring the tree into the ground.

Field-growing English Oak with a slanting form

.jpg)

Slanting form Hawthorn by Harry Harrington

Windswept Form

The windswept form is one of the most difficult forms to portray as a bonsai though is often one attempted by beginners for its dramatic features.

The windswept form is also one of the most misunderstood forms. The typical windswept bonsai is styled with all of its branches on one side of the trunk flung out towards one side by some invisible force! This cliche rather spoils the form but is often repeated.

Windswept Privet by Harry Harrington

Twin Trunk Forms

In the twin-trunk form, two upright trunks emerge from the same roots and divide into two trunks at the base. Both trunks (trees) should exhibit similar shapes and characteristics having grown together in the same environment. However it is important, that one trunk should be noticeably taller, thicker and stronger than the other as though it has received more sunlight and nutrients from the shared roots than the other trunk.

Individual branches from either trunk will barely grow inwards towards the other, instead they will reach outwards towards the light and create an overall triangular silhouette. Both trees will often form a single crown.

.jpg)

Lonicera nitida twin-trunk bonsai by Harry Harrington

The trunks can divide higher up the trunk in a variation of the candelabra form (see below). In this type of twin trunk, a low branch has become strong and vigorous enough to become a small trunk in its own right with its own apex.

.jpg)

Twin Trunk variation Hawthorn by Harry Harrington

This is a difficult variation to use convincingly. There must be a noticeable difference in diameter or age of the main trunk, the sub trunk and the branches. Thin trunked trees are not suitable.

Multiple Trunk Forms

A multi-trunked bonsai should have three or more odd-numbered trunks growing from the same root base. All the trunks should vary in height and accordingly girth. As with a twin-trunk the branches should grow outwards into the light and create an overall triangular shape and composite crown.

Naturally occurring clump or multi-trunk form

.jpg)

Siberian Elm Triple-Trunk Bonsai by Harry Harrington

Group Plantings

In this form a group of individual trees with their own root-systems are planted together in such a way as to create a miniature wood or forest. An odd number of trees should be used in a group planting unless the group consists of over 13 or 15 trees. Group plantings are created using trees of the same species which have fairly straight trunks of varying size and height. Though a group planting consists of many individual trees it should by styled as a whole and should create an overall irregular triangular shape.

.jpg)

Picea glauca var. albertiana ‘Conica’/Alberta Spruce Group Planting by Harry Harrington

Raft Form

This form is also referred to as the sinuous trunk form and replicates fallen trees whose upward pointing branches are able to grow and become a line of individual trees connected by a common rootsystem.

Essentially very similar to a group planting except for the fact that each tree is supported by the same connected rootsystem.

Cedrus/Cedar bonsai in Raft Form, styled by Harry Harrington. The ‘group’ comprises one tree that has been laid down in the soil and with 5 of its branches then trained upwards as trunks in a group.

Cascade Forms

This style is unusual in that the tip of the trunk is not the highest point of the tree. The image created is one of a tree growing out of the side of a cliff with the tree cascading downwards. A cascade can have a small head of upward growth.

As the natural tendency for trees is to grow upwards it can be very difficult to encourage vigour in a bonsai that is forced to grow downwards. Cascades are often attempted by beginners for their striking shape but it is rare to see good quality full cascades.

The cascade form is split into two variants, the full cascade has a tip that falls below the bottom of its pot, the semi-cascade is broadly speaking any tree whose trunk ends between the base and the rim of the pot. The semi-cascade form also includes trees with horizontal trunks that terminate at the roughly the same height as the rim of its pot. As with slanting forms, the roots should appear to anchor the tree with bigger, stronger roots on the opposite side to the lean of the trunk.

.jpg)

Crataegus/Hawthorn semi-cascade bonsai by Harry Harrington

Root Over Rock Forms

In these forms, the bonsai is either planted directly into a hole or depression of a porous piece of rock, or it is planted over a rock with its roots growing down into a pot filled with compost. These forms replicate trees in nature that endure an existence growing in rocky, mountainous regions and have to extend their rootsystems over barren rock to find enough sustenance to survive.

Root Over Rock Form English Elm by Harry Harrington

Literati

Also known as the bunjin form, the Literati takes its name from an elite class of Chinese scholars who practiced in the arts. Their paintings had abstract, calligraphic forms that depicted trees growing in mountainous landscapes.

These trees owe their distinctive shapes to harsh climatic conditions, they have long slender trunks that take many twists and turns and are the principal feature of the form. Bonsai in the literati form have very few branches that start very high up the trunk and carry just enough foliage to allow the tree to survive.

.jpg)

Literati Juniper by Harry Harrington

Candelabra Form

A tree in the candelabra form is reminiscent of an old tree in the mountains whose main trunk has died at some point in the past and a lower branch (or branches) has taken over and become a new trunk.

This form is characterised by a straight trunk that then has one or more strong upward growing branches (new trunks).

.jpg)

Candelabra form Juniper by Harry Harrington

Candelabra Pine photographed in Norway by NA Haagensen

This form is suitable for coniferous species often found growing near the snow-line in the mountains though it is also feasible for rugged deciduous species.